Must Be Oddum: Okinawan Black, Tea Kettle Tanuki & Slidey The Five-Legged Spidey

In which I follow the Buddha’s messengers and they lead me to the tea.

I made a new friend. An unexpected pal to say the least. Impossible, I’d surmise at any other point in my life. And yet, here we are. Buds. Mates.

I see him several times a day. He hangs just two arms lengths away from me whenever I’m at the helm of my writing station here in the Engawa. If only I could reach through the wall, I could touch him right now. Just past the amado storm doors. I slide them open in the mornings, bathing the tatami rooms and smiling baby dragon mugs with daylight, and slide them closed after dark, just as the salt-shaken stardust and golden moon slivers scratch open the night sky above these fingerling yato canyons that spread out of Sagami bay.

This motion is how he got his name: Slidey. He is, indeed a spidey, and he does, in fact, have five legs.

And so, you ask a few questions at once:

1. Why and how would you befriend a spider?

2. Didn’t you, in fact, watch Arachnophobia as a child and develop a blanket fear of all spideyz from that point forward?

3. What happened to the other three legs?

I’ll do what I can to address the first two, but the third I can only speculate. Born that way? Lopped off in a fight? Blown away in a bad wind storm? It’s possible I even slid them off in my klutz amado kerfuffling every day.

All I can say is that’s how he was when I met him and given the real estate his orb-shaped web occupies and how he fares during wind/rain storms, I think he’s done very well for himself despite having like 30% less legs than his brethren (p.s. I know he is not a female, because apparently those are the ones with the red/purplish belly jewels).

I’d like to say I befriended him because of this leg-lack, as a sort of moral obligation, but in fact, I was simply talking to him as a way to disarm a lifelong fear of spiders—the kind of fear that has gradually had to decline with visits to the bug shrine at Kenchoji and the sheer volume of large, hand-sized huntsman spiders that occasionally roam the halls of corridors across Kamakura and Japanese countryside writ-large.

I screamed at my first huntsman sighting and was promptly told that it was lucky to have one in the house. After all, they prey on cockroaches (nuisances) and centipedes (actual threat) as a kind of destroyer of all creepy-crawly evils. Nature’s rumbas, let’s say. Tank in the abode.

Slidey, though, is a Joro spider. Large and native to these parts, they have in recent years made their way to the United States, causing headlines about nightmare fodder. His neon body and long legs have a disco-enchanting aura and up until the past few months, I’d been far too paralyzed by fear to have looked them up, preferring to remain oblivious to danger and keep my dreams nightmare-free. It was only when I started chatting up Slidey and was encouraged by a long-time Kamakura resident to get familiar that I promptly did so.

And, how. You see, in Japan spiders are—as my keitai Japanese sensei explained in a newsletter of their own this week—お釈迦さまのお使い—aka messengers of the Buddha. Not just auspicious. Downright holy.

Here I was fearing them my whole life, no wonder it took so long for the dharma to sink in. Except, I don’t think I’m alone. I’ve had multiple foreign guests. All of whom are well-and-man’d up in the real world but shutter at the webs with dangly neon ornaments inside.

Yet I’ve found a little chatting, a little naming, and some long-overdue research has gone a long way. Long enough to find out they are messengers of the Buddha, in fact.

And what is the message of a five-legged spider?

Another way of asking the question: how could I pass up a chance to befriend perhaps the only 5-legged spider I’ll ever see? Guy is a celebrity, a legend, as far as I’m concerned. The least I could do is immortalize him in this here dispatch—after all, his lifecycle will be over soon, from what I gather, he will be gone by winter for good. So, let’s toast to Slidey, the five legged spidey, my first proper insect sensei.

I hereby promise, even as his web grows more ambitious by the day, that I shall not tinker with his trap even if I have to duck, or even crawl under it to properly operate the amado routine. The least I can do for this brave soul. And thanks to the friend who yelled at their child for squishing an ant indiscriminately with their finger that first reminded me: bugs are satient beings too. And if I am to liberate them all—from my shit—I gotta stop squashing their bodies and habitats.

So come on down mosquiteeez, take my blood, if you must. But I will squish you if you attack the soft flesh of my spawns. Thems the rules, I’ve been told.

I know what you’re thinking. It’s been too long between newsletters to suddenly subject my dear readers to esoteric bug stuff, but it’s been wavy over here. First baby fevers. Hand foot mouth diseases. Daycare shuttles. Chapter deadlines. Emotions nearly boiling over like unmonitored kettles.

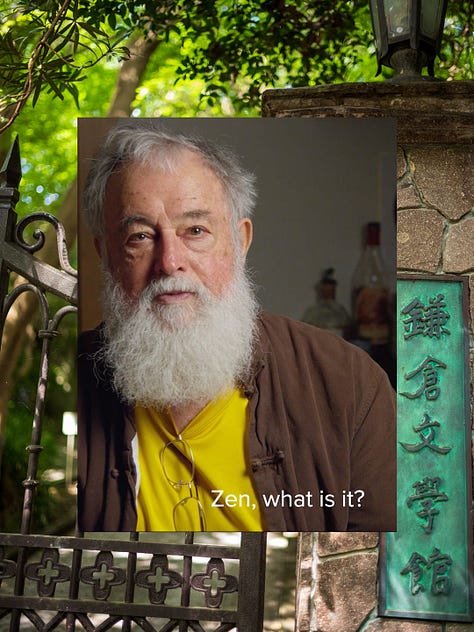

And yet, so much curiosity too. A screening of Dancing with the Dead: Red Pine and the Art of Translation—thanks to my fellow Subtea Subterfugist Nick Herman of Kaleidoscopic Mind fame— a documentary that would delight any tea lover (even GTH has a dian hong in his honor, fitting as he does drink some DH to kick off the film).

A monthly Writers Salon as promoted by the good people at SWET—a four decades+ organization supporting English-speaking writers, editors and translators here in Japan. Outstanding souls, the lot of them. I basked in an evening on the lamb, meeting a fellow Alex also working on ambitious short fiction, a chat over a recent ramen book with Florentyna Leow who also authored the memoir How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart, and got to build up anticipation with soon-to-be debut novelist Mike Fu who will release Masquerade next month.

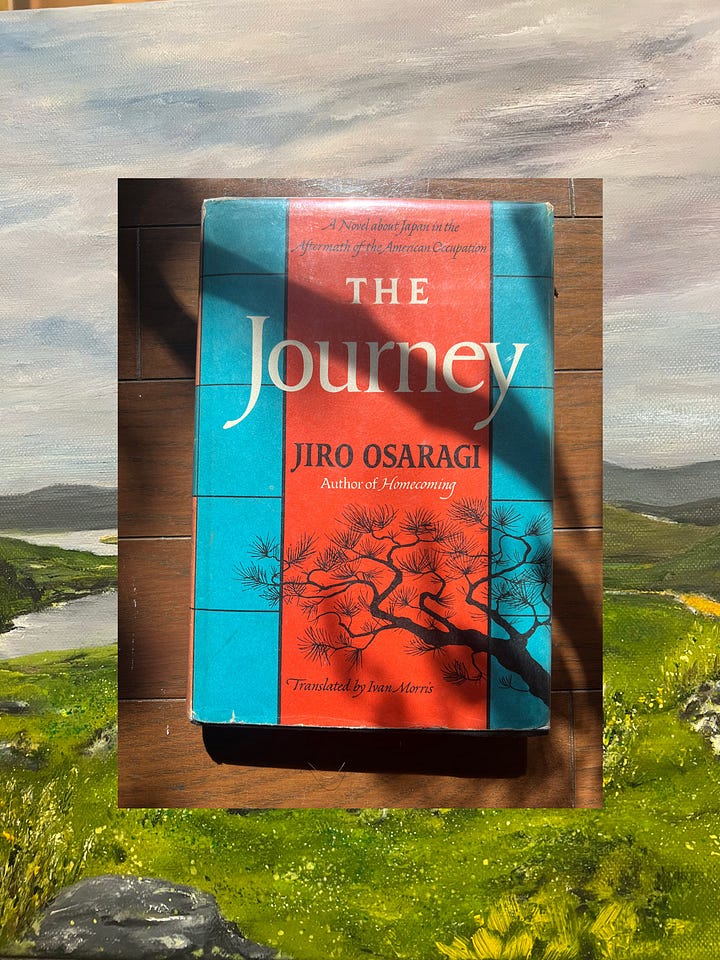

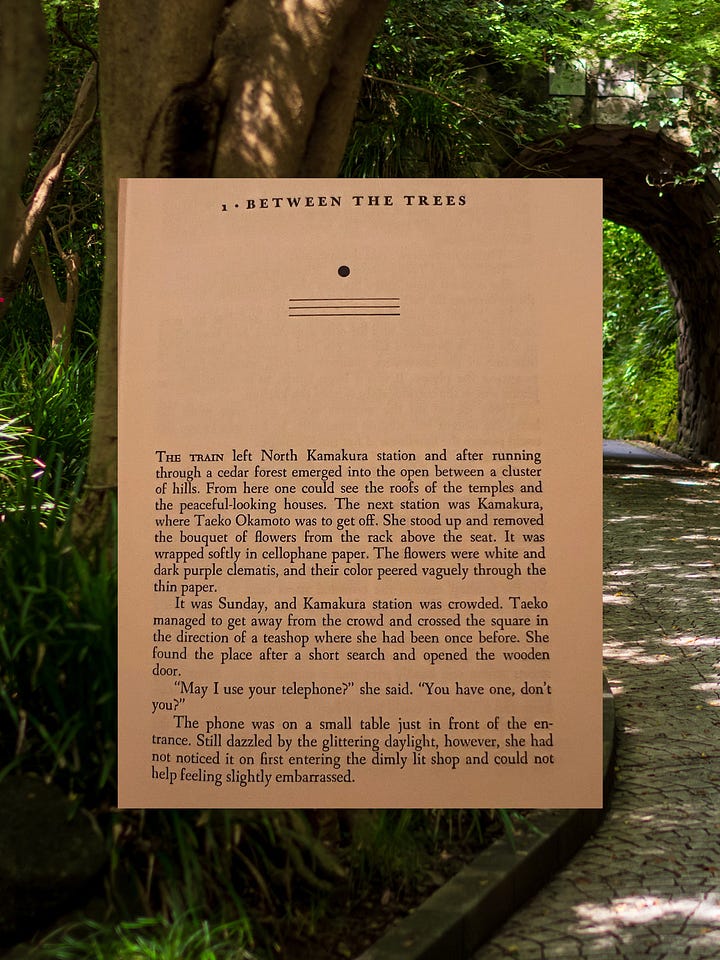

To the salon I only brought my half-formed thoughts about Substack and cold brew tea (a Miyazaki kamairicha I bought from Ten in Shimokitazawa and a Himalayan white from Chiyaba) to Bruce’s beautiful Salon space in Kitakamkura (now graced with a soothing painting of the Irish countryside by a recent guest). The host was gracious enough to lend me the elusive Jiro Osaragi hardcover The Journey, which I’d been craving since reading Homecoming this summer. By reading the first page I lost all the guzen marbles and gained new ones.

And leave it to Mark Schumacher— self-professed guide to spirits of both booze and buddha variety to bring some raw nihonshu (namazake) that really wet the whistle after 10,000 bottles of formula prep.

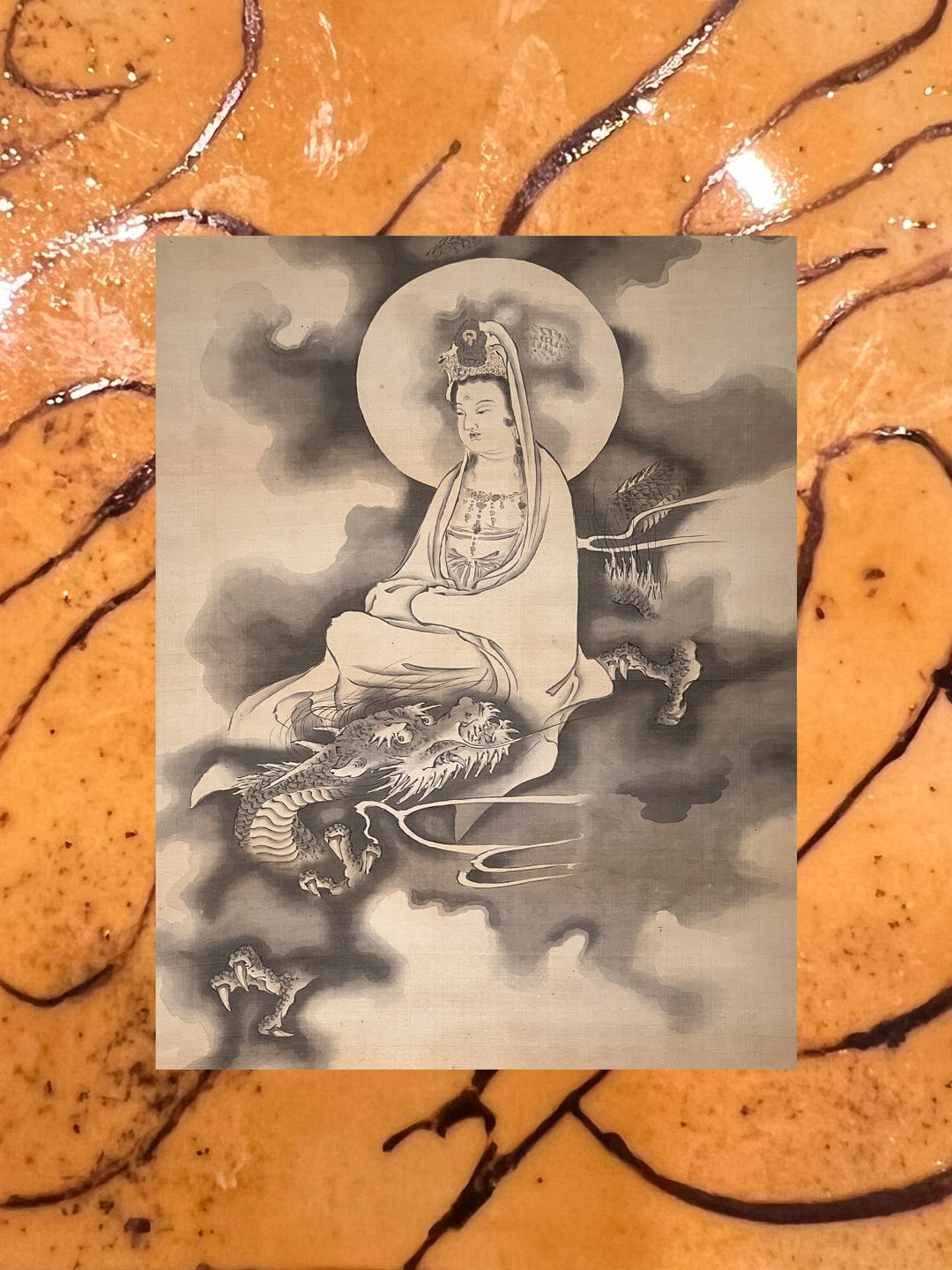

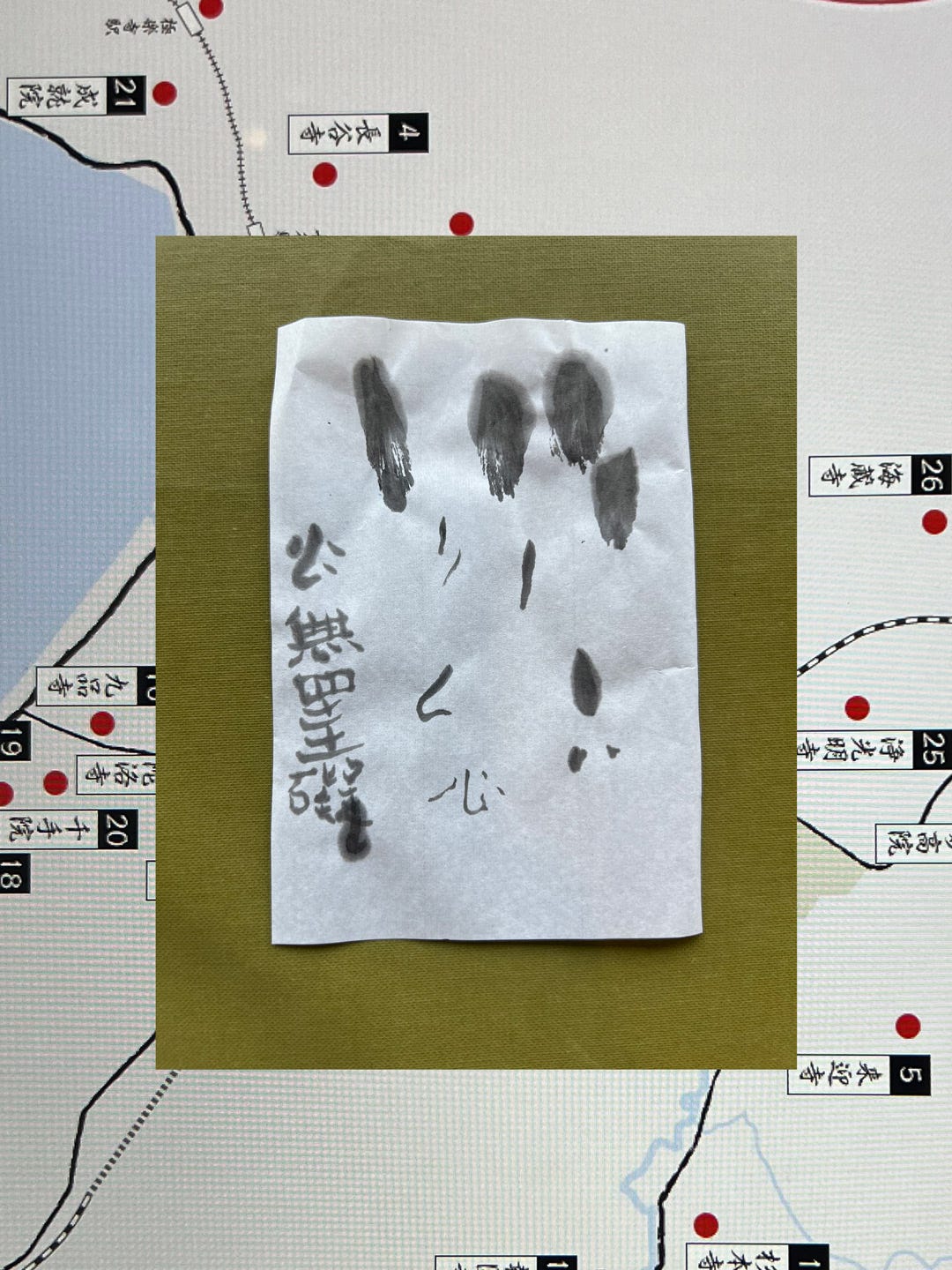

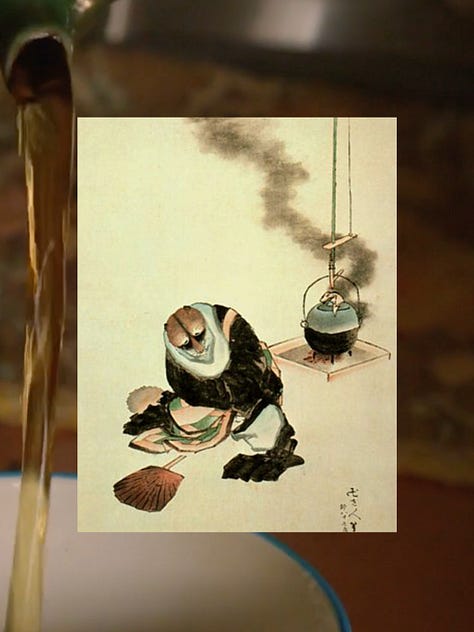

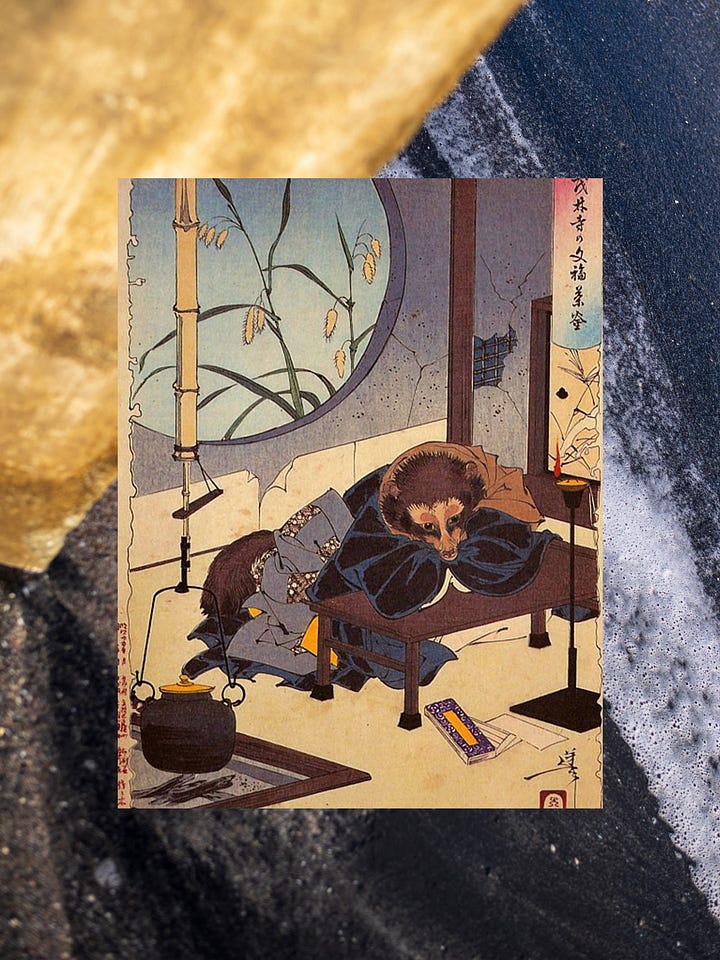

Mark—who I insisted write a book, or several, that places his incredible work on the AZ guide to Buddhist statuary in its rightful form—was generous enough to point me in the direction of his Tanuki article, specifically the part about the legend of the tanuki that turns into a tea kettle. The images herein should do the trick gist-wise, but please do visit his site and read the whole piece if you’ve been at all curious about tanuki, their lucky scrotums, sake bottles, straw hats or unpaid bills (really anything on Mark’s site is worth reading).

This whole fortnight, but the Salon especially, reinforced a sense that the creative souls I come into contact with here are one of a kind. It prompted me to consider presence as filter —as nature’s curator—and I wondered whether the people we come into contact with aren’t, after all, the most interesting people in the world.

Perhaps the hunt for the best, a slog I’ve been on my whole life, is nothing but the discovery for the thisest, the nowest, the herest, the thusest. I’ve learned more about art hanging out with my neighbor—and more about language and bugs in a single lunch with a friend—more about the perils and promise of writing than a single writers salon meeting—more about talking to the dead a single documentary screening than my culling of bests lists could ever.

It makes me cherish all that appears before me. It makes me want to read the writing of ten thousand rejected manuscripts. Hold tight the preciousness of rejection slips, like the rawness and realness of all that unpolished gems offer that editorialization often rubs away. If this is what the end of monoculture means, I welcome it. I welcome a world where the town poet and the town plumber are equals and appreciated as such. Where the distinction between art and life is seen for what it’s always been —an arty-faced artifice.

Is this only the magic of Kamakura at play? To unencumbered my heart before my first foolhardy brushstroke in the shakyo halls of Hasedera and getting to meet the laughing heads hidden behind the eleven-headed Kannon for the first time.

And if it is, so be it. Guess that’s why I’m here, glued as a dude to his board with the sharks a-swirlin.

And of course I’m still reading the new Sally Rooney and how she moves around her pawns and sex scenes and lawyers in her Irish interlocking Intermezzo’s and filling out my LA County absentee ballot, but I gaze less longingly at either than I do the fence of Osaragi Jiro’s teahouse just off Kamakura’s main drag or the web near my window.

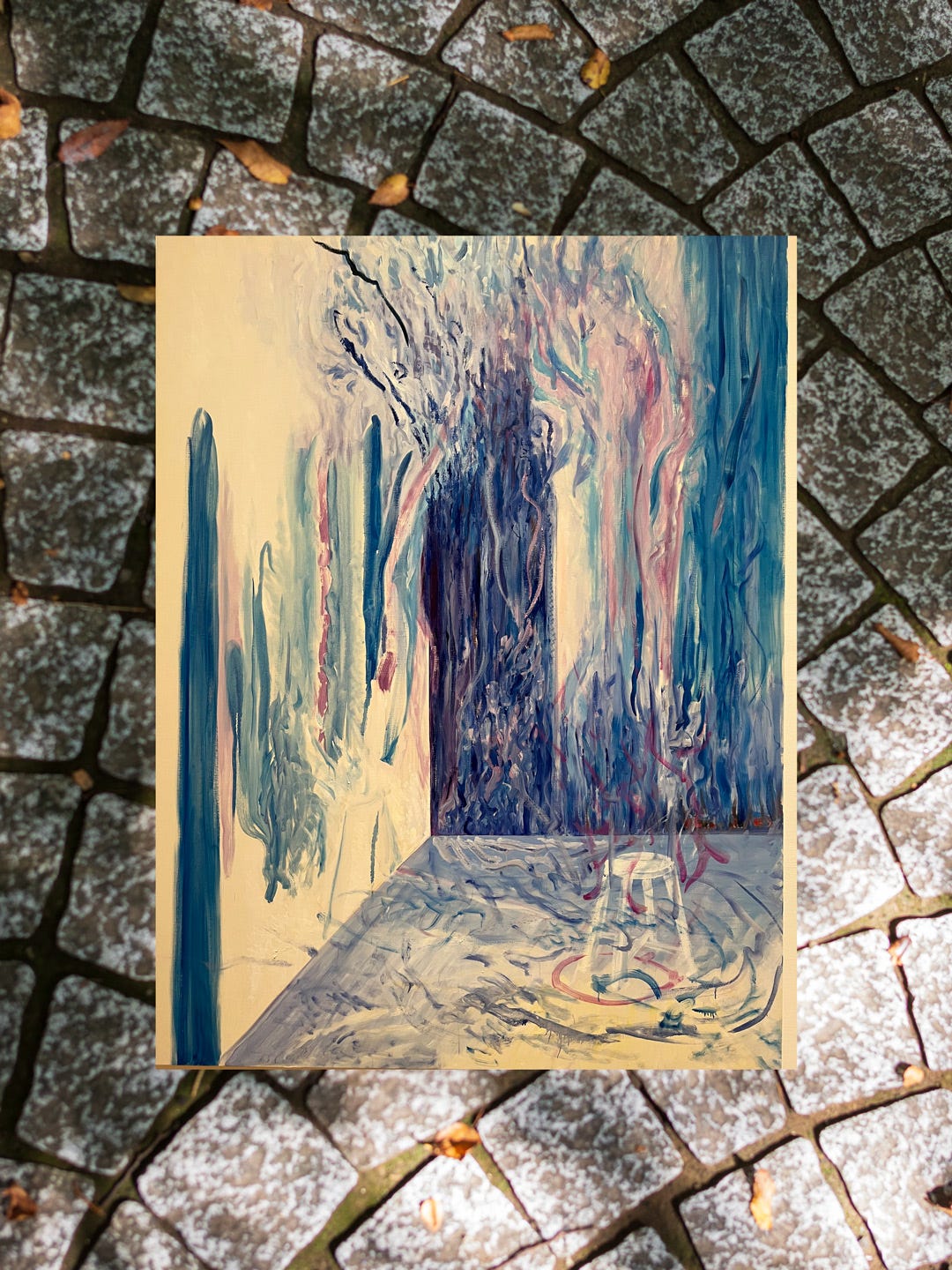

And see what happens when I wait too long between dispatches? I get so webbed-up with Slidey that I don’t even mention how outstanding the Ishida Takashi’s Between Tableau and Window exhibition was at The Museum of Modern Art Kamakura & Hayama—where one leaves questioning whether paintings are windows or windows are paintings or anything is anything as much as it as a process of everything that goes into it. And so, as usual, the images will have to suffice where the writing fails.

And so, at last, let’s get to the leaves.

Ever had a tea that never quite arrives? Like you’re on a trail, approaching a campfire. You can smell it. You can see the flame tips just over the knoll ahead. Spot the shadows on the stone wall. Hear the voices of those gathered. And yet, there is something in the flavor of that is anticipatory alone. That is never quite fulfilled in the arrival. A spell that breaks when you enter the party. When the present is unwrapped. When the last piece of cloth is discarded. When dawn breaks open the darkness of night or when night throws its cloak back over the light after dusk.

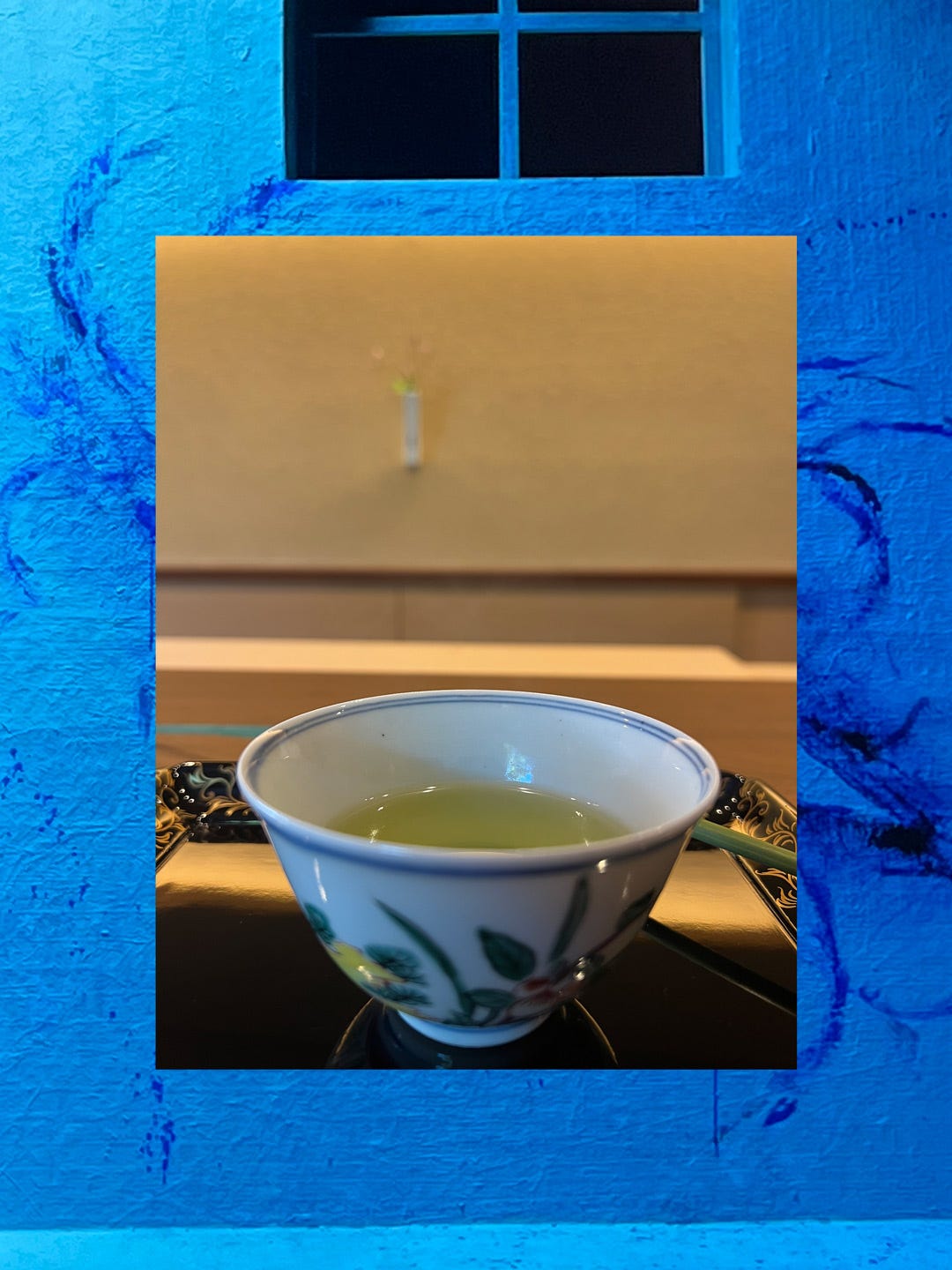

Last week, I received two small baggies of this tea from Kitajima San, the namesake chef of at my neighborhood kaiseki restaurant which relaunched recently after a fire the day after the Dragons hatched in mid-June.

This tea is produced by Okinawa Tea Factory. It is made from the Benimomare cultivar—created in India almost 100 years ago—by Tomoko Uchida, a tea maker trained in Sri Lanka. It is indeed grown in that island paradise of a prefecture I visited in January 2023 upon moving to Japan and partook in the ashtray-flavored-cartoonishness of bukubukucha (which I’ve as yet failed to write about) but I somehow missed that tea is actually grown there.

By not arriving, this tea epitomizes a certain kind of restraint that plays peek-a-boo behind pillars of Japanese culture. Once, Kitajima San was explaining to us the violence that certain levels of spice reeked upon his palette. He has an aversion to intensity. If tea and Zen are one flavor as my teachers and their hanging scrolls say, then it stands to reason that kaiseki cuisine itself—born as it is out of the tea ceremony—is built out of the shamanic bones of Zen. In other words, all flavor and spice—and for that matter portion size and sensory upheaval—is all poured through the filter of restraint. See shojin ryori. See the nearly salt-free food at a meditation retreat. See yasashii-aji, the description for kind taste, a word we have no approximate for in English, as decided upon by the power vested in me by the pair of recent visitors to the tearoom.

What makes it through the sieve then points, alludes, suggests, and tantalizes as much or more than it’s meant to satiate, satisfy, or insist. In a loud, battering-ram of a world, this is to blow the mind by not even needing to blow off the heat of the soup. The temperature is already perfect. In other words, it’s all soft landings, all the way down. In a sense, this tea would suit Kitajima San’s palette and his genius—if I leave his kaiseki counter feeling like I’ve not yet fully arrived, that there is more just around the curtain, on the next 300-year-old plate, the next creative concoction, then how could I not want to come back and try to get that much closer to alpha?

I left the third steeping of this tea as long as I dare with black tea. It’s a long, beamy tea. A tea that makes you forget how often black teas bite. A patient friendly brew with a smile that says, ‘tell me everything, don’t leave anything out. I’ve got the time.’ It bared no fangs. A spider whose bites are like kisses. A spider like a child. A cute, bouncing spider of a tea. Essence of Slidey, in a cup.

Apologies folks. Like life, I will occasionally disturb in my joyrides. There are bumps in the road. Sobé it, my fellow lizard logo lovers. Whether you prefer your teas burlesque, full nude, or whatever is on display down a dark alley near you, I hold not a drop of judgement.

To all those who’s high school friends gifted them old Sobé bottles filled with shaving cream and food coloring to create a kind of truck-stop, trash-culture magic lava-lamp without the need for a lightbulb, I salute you. I salute myself.

And I salute Slidey and all five of his otherworldly legs, doing the job of all eight immortals.

Corner Seat on Wet Mountain

Capturing slack jawed surprise

Hidden in strings of saliva

Beneath buzzsawed humdrum

Of rotten milk fingernails

And hypnotist spin geometry

By real web masters

Depends not on aperture clicks

But on questions.

When a book is a real chair burner

Should it come with a warning label?

When a window might be painted

Should we try wiggling the handle?

Just to be sure…

Just in case…

Just a minute…

Our orientation to solverhood

Can turn obstacles into offerings

And threats into awe string

Quintets

Played by a single, Slidey

misunderstood instrumentalist

messenger.