The Story of the Bambino Chawan: Obits, Oshaka Samas & Omachi Gods

In which I attempt to drain my stash in anticipation of an influx, doing all I can to keep this under 6000 degrees.

Can you still find the rainbows glowing in your tea cups? Hope so. Truly, hope so.

Wrote my debut obituary this month. There. Came right out and said it. Hard part first.

The subject was a brilliant art curator, a ghostwriting client, and above all, a friend. Someone I greatly admired. I wrote more drafts from his perspective than on any other project I’ve been a part of. Mostly, it was a joy to be immersed in his experience but if you, like me, can’t ignore the gaping pit between these words, you might have guessed that this was a book that was never finished (and least not yet). Never fully drafted. Caught in an agent—publisher—author cyclone for much of the last decade.

And, more than anything, it breaks my heart that this man never got read a complete version of the story. Will anyone? We’ve already lost one reader. For me, I’m realizing, that’s already one too many.

I’ve given eulogies but had to do a bit of research about does and does not go into a proper obit. It was my honor to be asked to write it and I did everything I could to paint a picture of the deceased. Yet you can only do so much with several hundred words. All along, I felt the crushing weight of the thousands that have been written—and have yet to be written—about this man and his extraordinary life.

The silver lining is that the experience also gave me a timely push to continue my main ghostwriting project of 2025: the project of re-articulating my ghostwriting philosophy following 12 years and 25 books into the game. Now, more than ever, I believe in books. I believe books are vehicles for transformation. But if a book is going to be transformative to a readership, it must first be transformative for the author. This isn’t my way. My idea. This is the way as its been illuminated for me.

There are better writers out there. Better ghosts too, surely. But you can put me in a room with anyone on this planet who has a sincere desire to write a book and I promise I can help them excavate, discover, and articulate their truth. That’s what my new project seeks to offer to those who are ready. To those willing to get wet.

And, though he will not read these words either, I do want to thank the friend who passed on for reminding me once more that time is a real thing. Our lives expire. Our loved ones stay behind. And there is an invisible stack of books next to my bed—all those stories my own loved ones never wrote down. I would do anything to read even just one book in that stack. Maybe part of my mission is to make that collective stack of ghost books that wanted to be but weren’t just a bit shorter.

For this month’s poem, I wrote about all the things that don’t fit into an obit. You can read about it below the updates and lengthy story about my making a tea bowl.

In tea news, my gleekers are gleeking and my tongue is tingling. I’m eagerly awaiting shincha season, which will begin later this month and continue through June. You can read my report of 2024 Shincha here and the part one and two and three and four from 2023 here. A 2025 edition will, surely, come around June.

Also, it’s been a couple years since I’ve had Chinese shincha—or first pluck green tea—so I’m also having a friend who lives in Hangzhou shepherd over my favorite three Chinese greens when he comes to visit next week. They are: 竹叶青明前特级静心四川峨眉山, 氷川秀芽明前重庆氷川, & 西湖龙井明前特和一级狮峰 — which, for the record, is Zhuyeqing from Emei Shan in Sichuan, Yongchuan from Chongqing and the famed West Lake Dragon Well from Lion Peak. I’ve asked for small amounts of better teas, a trend I’d like to continue in all tea buying going forward.

In the meantime, I’ve been actively trying to do the opposite of buying tea. Your boy has been at work. Draining my stash.

Woah. Don’t fall off your wobble stool my droogs. Not that kinda drain. Not that kinda stash.

It’s time, as the cherry blossoms begin to fall, to tell you a story about Halloween candy.

“But Dweez,” you protest. “Don’t do this to us. Don’t yank us by our readerly necks and make our noggins eggnog foggy at all the wrong times of year—let’s behold instead the sakura. They are just a breeze away.”

Let’s split the difference. Best I can do. Long enough story of the tea bowl, I suppose. So the following will be briefer.

You see, I hoarder hides in me. Even after several years of watching Halloween candy rot—saving all the best pieces for last. Even after the most treasured of Halloween candies were attacked in a box under my bed by a family of mice. The hoarder lived. Still lives.

Where to take this hoarder? Where to go to show him why we need to drain the stash? Need to shed the snakey skin so all that is new (or. especially, and properly aged and old) can come in?

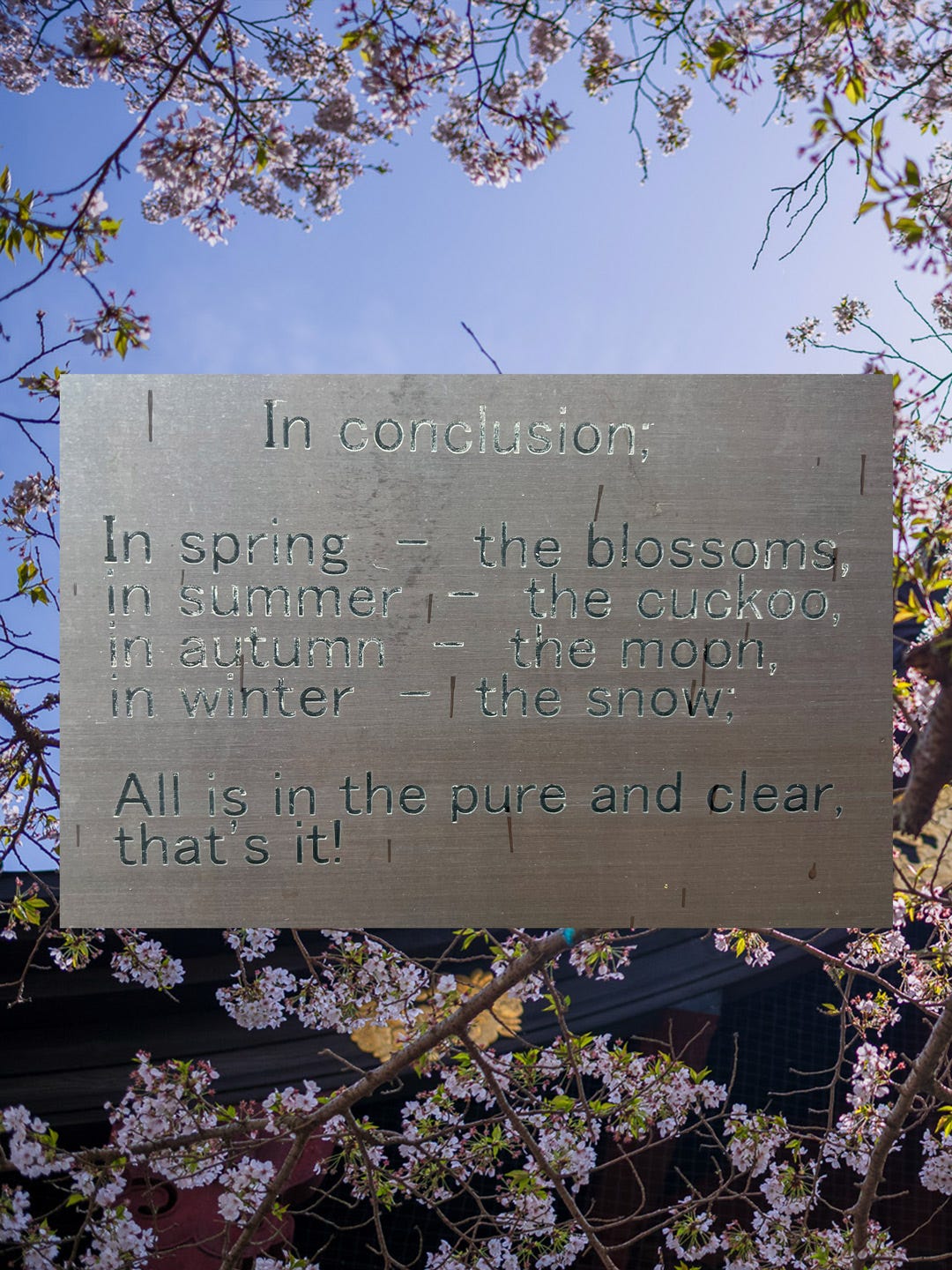

They say a canopy of cherry blossoms will do something to you if you let it. If you arrive early enough in the morning so you’re alone or you can do one better and ignore the selfie sticks. Or if you can do one better and see the joy in the young and the old and the sheek and the slacked. Let yourself be captivated by the branches sagging under the featherlight weight of all that nothingsomethingness. And then you look at the land and want to own a piece of it. Without a doubt with its own little sakura on the ranch. A whitish pink piece of this paradise. Then realizing that if you don’t have it already, then you’ll never have it. Which, suddenly, makes you have it. Like it appeared in you hairy potter’s pocket.

Spring, you are a real Charles Dickens.

So what I’m saying is that I’ve slapped a “No New Tea” sign on my chatansu. Focusing on drinking teas I’ve been saving. Slurping samples I’ve forgotten about. Pouring it all up and guzzling it all down. No haul sacred. Nothing saved for a special occasion.

Meanwhile, I’m taking in no new leaf. I even chopped down my GTH sub to magazine-only so as to accelerate my cupboards getting real, real bare.

You see, if I’ve learned anything from Shincha season it’s that the influx is real and if there is anything leftover from the previous campaign, it will be forgotten and ignored and otherwise disrespected.

Also, though, if I’ve learned anything from this collision of way-too-much tea drinking period of my life and this way-too-little time to be drinking period, it’s that nothing but the best will do. And I plan to be much more discerning before purchasing tea—shincha or otherwise—going forward. Lower amounts. Higher qualities.

After all, I might only have so many cups left.

This dispatch is coming a bit latter than my current target of beginning of the month, reflecting on the past month. Forgive me. I’ve been sidetracked by many things. Most recently an innocent request for a Baile Funk primer by a couple of my Kamakura comrades. But to do that, you need a Brazilian music primer. And now I’ve got myself 38 songs into something quite more considerable than I planned.

Unfortunately, there are far too many songs that I have only mislabeled snippets of in iTunes folders from 2008. Not your legit Spotify-able fare. One of the songs that simply does not exist on these more formalized platforms is the 90s classic “C.I.D.A.D.E.D.E.D.E.U.S.” by Cidinho & Doca. This song played more times than I can count in my shoebox sized Botafogo apartment all those years ago when I was mostly looking for bad times in narrow places.

Oh what?

You want to keep this party going. That kinda attitude makes my hopped up tea self want to listen to glamarosa while we’re at it:

Apart from far too many hours on Brazilian music playlist construction work sites, I’ve still been boiling tea. Wrapping up the GTH course by the same name this week. Happy to report that the tea that’s surprised me most boiled was a trifecta of sannenbancha’s that I served to Alba, the cohost of my forthcoming (I promise) Tea in Japan podcast. Sannenbancha is made several ways: collect three harvests over three years and blend, harvest then let it sit for three years, or some combination. I blended three sannenbanchas from three regions: Miyazaki, Shizuoka and Nara. The result was outstanding.

The question at hand at the time of drinking was this: what does it mean to be tea drunk?

I can’t put my finger on it but one sip of a multi-hour boil of my sannenbancha blend did the trick. I went from being a guy in a room trying to make a podcast to being the inside of a log on a pile of other logs. The whole lot of us logs fully aflame. Like bonfire, status. And yet, somehow, we middle of the middle logs were not yet on-fire. Stay with me here: I was inside the very core center of the log. Like an apple core, but a log. A log core. If this blend for boiling had a name it would be: Log Core. Or if you are stonier, picture those rocks in the dry sauna, repelling water within seconds of being doused. That’s you. That’s me. That’s us. An imperious form to exist as. At once wet and dry. Drunkenness as fibrous clarity of form. A life lived with no fear of going up in flames even as the fangs of fire draw near to your supple flesh. Drunkeness as being the opposite of twisted or tipsy but upright and clear and ironed out like a brand of spangled banner worthy of swinging overhead. Drunk as opposite of drunk. Tapped in instead of tapped out. So much so that you don’t even link the gardens. You just throw up a piece sign and roll out of the room like a log down a hill toward a fiery destiny.

You can hear the drunkenness live and direct on podcast near you very soon. Just have to rescue the audio. We always knew a tea podcast was going to have a quiet vibe. Just not this quiet. Yamsayin?

In other news, I pitched a couple stories to the Japan Times and made it most of the way through the publication’s Culture Editor’s outstanding novel Masquerade. Mike is generous and patient with his characters, two traits I admire and seek to build in now burgeoning longform prose. Now clocking in around 25,000 words. We’re on the way.

I also got a chance to see the deservedly lauded and impossibly crowded Ryuichi Sakamoto “seeing sound, hearing time” exhibition in Tokyo. Special to see the real-life tsunami-surviving piano that featured in the 2017 documentary CODA. That film, maybe my favorite I’ve ever seen about music/sound, introduced me both to Sakamoto’s work and also what I’m calling “Lived Essentialism” as an artistic way of being.

I also got to fulfill a long-held dream of visiting a Kamakura literary idol Osaragi Jiro’s Yukinoshita tea house, which is now open as a café on Saturday and Sundays. I wrote him a kind of prayer in the guest book hoping that it gets to the other side. The author played an instrumental role in preserving the environmental beauty of Kamakura, and by extension, all of Japan. I even got a list of volunteer opportunities to play my own tiny tiny role in keeping those spaces as beautiful as they are now.

I also slurped noodle and dunked tempura at a rad Jazz & Soba event in Gokurakuji at Taguru, featuring some excellent musicians that frequently play in the era: DJ Toru Hashimoto of Suburbia fame and Jazzy Sport’s Marter & Tsuyoshi Kosuga. Kosuga is a genuinely cool cat (and stellar guitar player, trained at Berkley in Boston) who runs a bring-your-own-vinyl night out of Sri Lankan Curry outpost Lighthouse in Hase. Kamakura is flush with good music for a town of its size. Delighted to have events like these in the hood.

In convenience news, the Lawson down the street celebrated a 30th anniversary in fashion and Shohei Otani is happily selling Ocha out of vending machines everywhere I look, proudly in his Dodger blue. All of Japan, really, is now Dodger blue.

But, of course, much of this month, between the rains, we basked fully in the cherry blossoms that are popping up and blowing away on every hillside and street corner across Kamakura—and, probably, the whole country. It really does all come and go so fast. Doesn’t it?

Now, then, who wants to hear a story about a bowl?

As you look at me askance— with my circular etchings squarely in my full-blast Buzz Killington era—let me just say that there are a lot of bowls out there. I get it. But, no bowl, you must understand, is quite like this bowl. I promise.

From the moment I was introduced to My Neighbor Sergio, I became impossibly curious about both his way of art and his way of art-making. Since those first early conversations, he’s humored my 10,000 questions and even helped me make my first kakejiku hanging scroll. Outside of the lot I live with, there is no human I’ve spent more time with during my two years in Japan.

So, of course, when Sergio mentioned that his next exhibition would be entirely of chawan (tea bowls), I had the audacity to ask whether I could get in on the action. Ever generous, he accepted. Then, on one cold day in mid-January he rolled by on the bicycle and told me that the time had come. I threw plans aside and I hiked the four houses away to his studio.

I didn’t know it then, but the experience would come in four distinct phases: Building, Rebuilding, Glazing, Burning & Bowling. Which I will now, at length, describe.

Building

That first day was a microcosm of all my apprentice-space-ships in this Kamakura voyage. In other words, it was the interpretive dance of joy and despair by a fool who thinks he can swallow every drop of amacha falling from the sky on Oshaka Sama’s birthday.

I feel it betrays the spirit of our dynamic to snap too many photos throughout, but I followed Sergio’s advice of starting a ceramics journal on the onset of this aimless, endless roll down the bowling lane. Picture me like a slumped like a doofus on a stool a few inches off the ground. A lifetime of instruments splayed out in front of me. Jot down the dozen-odd sizing parameters that a chawan ought to fall into. At least the ones I can catch or remember. Try not to get mesmerized by the professional working across from me.

Try, most of all, to do everything very, very slowly.

Apart from a high school class where I made a mask that greets anyone who visits the tearoom—a reminder never to take any of these too seriously (and I do mean ANY of it)—I’d made pottery exactly three times. Once, the November before we moved, at Still Life in DTLA on an electric wheel. Once here in town at a studio in Hase a month or so after we arrived in Kamakura, also powered by an electric wheel. Then, this past Christmas, our whole merry band huddled into Takara Clay Studio in Kitakamkura, in the same garden where I take Senchado classes, where we saw what we could whip up sans-electric wheel. Those finished pieces I need to pick up later this month.

You could say that during each occasion, I tip-toed a step closer toward that cliff that gives way to ceramic obsessive abyss. It’s maniacal enough to collect and study these godly wares on tea side-quests. It’s quite another to get hooked, lined, and sunk by the spider’s thread dangling by the ceramic deities looking to harvest their next shock trooper.

What I’m saying, friends, is maybe it’s me. Maybe it’s me after all. The mirror won’t show it, but I taste metal skewering through the flesh of my cheek.

Back at Sergios, we were off no-wheel freewheeling. By hand, they say. As it used to be, they say. For this first chawan, I worked with mashiko clay from Tochigi Prefecture (northeast of Kamakura/Tokyo also haunt of Shoji Hamada of Mingei/Folks Craft Museum and Unknown Craftsman fame) which is grainy but balanced and easy to work with. Forgiving.

Call me cliché. Call me obvious. But you can’t call me a liar. Having a grainy pile of squishy earth in your hands offers an antidote to this black mirrored world that few things do so concretely and completely. Before long, I was fully lost in the sauce. Adrift.

In prior pottery experiences, I had been restricted to an hour. That first day alone, I spent 3 hours shaping the form. Full of mistakes, to be sure. I forgot to leave enough clay for a bottom and foot. Which I had to repair by slapping on another 100 grams of clay (which, when you’re aiming for 350g weight at the end, but you started with 500, is tricky). I also lost concentration using a wooden foot tool and pushed too hard with my hand holding the bowl steady, causing the whole operation to get a pretty wavy lean. As I tried to remedy this, I neglected the foot I had just been working on, so that became warped too. I consistently cracked the rim, which I made too thin too fast, and, eventually, started to stress out about all these rookie mistakes (despite my rookie status, mind you)—all of which left me to add in the notebook that I should definitely have some hot tea near me at all times as I work to shape and build a chawan for three hours in a frigid studio. A calming fuel. Steady. Tea as slow grease.

When darkness fell that first day, I wasn’t quite done. Bowl was big. Shape was wonky. I had more work to do and planned to return ASAP. I was told the bowl would be OK if left covered for a few days.

Rebuilding

A month passed before I could make it back to Sergios. There were illnesses and other setbacks, as I’ve written about. My sensei did what he could to keep my bowl alive. The chief challenge, as I understood it, was to keep the clay from drying out. He would sprinkle water here and there—and it probably helped it was raining quite a bit.

Still, a full 30-days later, I sauntered back into the studio to find not a wonkily-shaped bowl but the memory of one having collapsed into a dozen or so pieces. In essence, a shattered bowl before it even came into being.

This was the first of three major setbacks to the bowl’s right to exist.

I thought it was done for. Sergio was more patient. Always patient. Slowly, slowly, he showed me how to wet the clay and cradle the splayed-out-pieces back together. Three more hours and thirty minutes later, it became a kind of shape again. Again, I used too much of the bottom clay. Again, that necessitated adding more for a foot. My bowl swoll ever larger, at the edge of all the permissible parameters to still be a called a chawan.

I came back the very next day for another 3 hours. Sergo armed me with different tools—of various shapes, sizes and materials—to shave down the bowl. Always slowly, slowly, slowly. The weight went from 880g to 575g, wet (it shrinks some in the first biscuit-burning). Sergio, forever blowing my mind, rifled through Moroccan, Tibetan, and Greek techniques as he worked on the bowls for his collection across from me, stopping patiently to show me how to employ these various methods.

Eventually, after my third 3-hour-plus session of building, I had a shape—from weight to foot to walls—that fell into the parameters. For a moment, I thought Sergio was just being kind to my zombie bowl but when we whipped out a ruler to check I could see he was right. I was astonished. Honored. Humbled. Amazed.

The bowl, like me, had survived the terrible January. The illnesses of body and mind. It had lived. By George, we had lived.

I did as I was told and brought it home to dry.

“It’s your bambino,” Sergio told me, and I believed him. How could I not?

Glazing

I kept my bambino in my tearoom, away from the elements. I checked it occasionally for cracks. It had been through a lot. Shaped. Fell apart. Shaped again. It had already spent about 11 hours in my hands in the building phase alone. Now it spent 10 days drying.

I brought it back to Sergio’s on a rainy day. We looked at the bowls from the first half of his collection. His work never ceases to astonish me and these chawan were no different. He let examine each one and we talked about them—their shapes, designs, clays, glazes—together. My jaw, agape, almost the whole time.

Like the bakery Pide down the street, I am beginning to lose the ability to tell whether I love these creative Omachi offerings—Pide’s bread, Sergio’s art—because I am getting to know the people so well, or whether I am getting to know the people so well because I fell in love with their creations. Perhaps it doesn’t matter. Perhaps there is no separation between them. In either scenario, I have my favorite bakery and my favorite artist just a few minutes’ walk away at all times. What more could I ask for?

Rain meant planning time to be there for the biscuit firing was too difficult. Sergio graciously fired my bambino chawan with the second half of his pieces and soon, the time had come to glaze.

By then, it was the end of the March—my chawan was more than 2 months in the making. I went up to glaze on a hot day and spent a full two hours considering, preparing and deciding to dunk my chawan by hand into two colors—something blueish and something yellowish. If I get into the weeds on my color choices we’ll be here for even longer, but let’s just say I considered it a hot/cold accompanying piece to join my hanging scroll. Part of a collective homage to my double dragons.

Before the dunking (there was also an entire menu of other glazing techniques we rifled through), we sanded down some rough patches. I decided I wanted to try to use my right hand for one color and my left hand for another. It was a similar balancing act I used when I made the hanging scroll—a kind of tapping into the more sensitive, exacting side and the more flowing, equanimous side. Also a way that I get to loop my inner family into the process, a practice that’s always ongoing.

I went with the right (dominant) hand first. It was smooth. Careful. Graceful. Almost crisp. The whole glazing process happens in what feels like an instant. There is no color, then, with a splash, it arrives.

I switched hands and colors. I didn’t know it then, but my second of three disasters was about to strike. If the first one—the bowl falling apart in my month of neglect— was a slow-motion disaster, this one was instant. It all happened in a matter of milliseconds.

Sergio had warned me. About how different glazes interacted with my clay. About absorption rates. The one time I was supposed to move fast—during a process where Sergio’s words of “slowly, slowly” rang in my head like a mantra—I could not do it. My left hand didn’t listen. You could say my inner child, the one holding the bowl, froze. Caught. As a kid, the one piece of ceramic that broke in our house more than any other was the handle of the cookie jar.

I kid you not.

We—especially me—made terrible thieves. Thieves that broke chimneys on cookie houses and had to glue them back into place. And so, all these years later, I was caught again. Hand in the cookie jar. I went in too slow, came out too slow, and tried to drain the color too slow.

The result was a disaster. The second glaze was so much thicker than the first that the usability—to say nothing of the aesthetics—had been comprised. A part of me, the same part that wanted to throw in the towel when I saw how my original shape had fallen to pieces, wanted to chalk up this as another NOOB mistake. Something to learn from but not something to salvaged. A bowl—that had been a zombie and a bambino—to walk away from. A bowl bid adieu. A ciao ciao chawan.

Sergio, yet again, remained patient. Calm. Relatively quiet, he moved before his mouth did. A scraper. A smudging. A borrowing from however many hundreds or thousands of past ceramic experiences.

Then, suddenly, after only a couple of minutes a new technique.

My bowl, instead of two distinct colors, now had two distinct styles. Two distinct universes, joined into one. To say it had a dramatic and staggering injection of character would be an understatement. A bowl that might have been a mere two-tone, blossomed into something dynamic, rugged, and alive. It had momentum. It had a will and determination to exist. It was beautiful. Singular. Glazed and glorious.

Firing

On Buddha’s birthday, April 8, the bowl was fired. I won’t divulge all the details about Sergio’s operation—and in truth, I can’t, because I’m still learning about how it all works—but it’s enough to say that the man has a gas kiln on site.

A firing is an all-day job. So many adjustments. So much measurement. Last year, as he prepared for his Sankeien exhibition, I went up and watched how carefully he monitored the climbing temperature. More gas here, less air there, it’s a 12-hour-or-more dance to make sure it all goes, ‘slowly, slowly,’ up to the desired temperature.

I brought one of the boys with me, strapped on my back. The first time this dragon saw fire; the flames were licking like a wild tongue out of the top of the kiln. To watch Sergio San work the fire is to watch the most intense—and the most dangerous—part of the ceramics process worked by someone paradoxically at ease and on guard. Not so much talking. Lots of adjusting. Measuring. Writing. Monitoring.

Different glazes melt at different temperatures. Different clays can survive different temperatures. He’s used dozen of combinations for this collection and they all had a sweet spot he aimed for. The flames were bright, then dark, then white. There was black smoke, then none. He was listening for the right sounds, the same way he does when he flicks a bowl to hear how it rings. Sergio told me that so many of the masters he has studied under here in Japan and all over the world can tell the temperature from the colors of the flames in the fire.

I have been both attracted to and repelled by fire my whole life. Afraid of the clicks on a tiny camping stove. Willing to build a bonfire taller than a soccer goal. This tension is part of how I know ceramics will be part of my life in the future—the same that existed in tea. A seemingly natural distaste for “tradition” and a longing for something real, solid, and true that has passed the test of time. I grew up where tradition meant little more than a tiny piece of burned ski pass string tied around a chairlift seat on a ski slope to prove you had been there the season before.

Things were going quite smoothly during the firing until the temperature climb grew stubborn. The air got sucked out of our light conversation. My son, who had been quiet, suddenly started kicking and screaming. Maybe he could read the air?

Something was wrong.

Only a few dozen degrees away from the finish line, the kiln had stalled. In trying to find a way around the wall—through adjusting all the variables—the temperature actually started to fall. Not good. Half of his collection was suddenly compromised. Maybe the kiln was packed too full of material.

“Maybe your big-ass bambino bowl is part of the problem,” a part of me popped up to say. I lingering guilt that Sergio has been willing to let me tag along for this journey shrouded over my heart. Half of his work was under threat, and I began to wonder, if it was all because of me.

Then, the third major disaster happened. The flames threatened to come out in the reverse direction. Really, really, not good. Sergio had to act quickly and shut the kiln off. The kiln still growed orange, but the temperature dive accelerated.

My fear of the fire—and my fatherly instinct—got the better of me and I actually jump behind a wall for safety. I watch a few pieces of ash float by. Something that, I surmise, cannot be a pleasant development.

At this point, I was not just worried about whether my bowl would survive—or whether all of Sergio’s pieces would remain unscathed—but I started to reconsider the entire practice of ceramics. This literal playing with fire. Part of my respect for Sergio is that—as a man in his mid-70s—he does all of these phases himself. Constantly testing and experimenting and releasing beautiful work, year after year. Ceramics, as much as it pleases my inner children, is not child’s play. It is as involved an art form closer to filmmaking than writing or painting. Storyboards and screenplays are just part of that process. The actual doing of the thing is a massive operation.

Also, there are probably “safer” approaches but is it any wonder that the pieces out of those operations lack a certain character? Any wonder that more sterile conditions would produce more sterile pieces?

Putting aside the danger factor, is all the sheer effort worth it for a few bowls to make tea out of? This level of investment of time? This risk? Are the rewards worth it?

By then I had poured some 15 hours of my life into that bowl—and I had been guided by someone with a lifetime of accumulated knowledge, experience, and expertise. I didn’t even source or sift or mix the clay or glaze myself to say nothing of the managing the kiln or other tools. This was months of work for Sergio coming after a lifetime of work. It was staggering to think of the time and effort spend to have the privledge of making something this way.

We had now arrived at the third of the three disasters. It was no longer about what was to become of my first chawan—or Sergio’s pieces—but what’s to become of my foray into ceramics altogether?

As these fears and questions swirl, Sergio moved ever calmly. Patiently. A change of technique—and then, not at all ironically, a sort of prayer: “Now we need the help of the kami.”

In his words I hear the spirit of a creator who knows how much is up to him and how much is not. An artist who knows every artwork is a collaboration. A ceramicist who, even with an encyclopedic knowledge of material and technique, accepts and surrenders to the fact that every phase of every pieces is different. That no two clays, glazes, kilns, firings, or bowls are the same. In fact, that is part of the appeal. A feature not a flaw of the work.

I hear someone who has found that elusive balance so many of us seek with our work: to give everything you can to make something beautiful and have only the faintest thread of attachment to the result.

A tiny, almost transparent spider web from the heavens holding the full weight of the aspirations inside every man. An impossible tension to survive. A tension that holds all the cosmos together.

When ten minutes had passed, the temperature began, almost miraculously to climb. The violent sound of the fire paved into a pleasant purr. The kami had come to the kiln. Was it any wonder? There were three cups of offerings placed in front of the chimney.

Forty minutes later, the fire reached the desired temperature. The pieces had made it. A blossom from Sergio’s cherry tree floated down near my feet. In just an hour, it was as if the sky had been empty—then filled wish ash—and now the ashes had been transformed into delicate flower petals.

I tried to express how impressed I am with the way Sergio handled the moment. How he averted disaster. He told me that being a ceramicist was like being a climber. At some point, you are faced with choices: make it to the top or go back. Live or die.

For me, it was all so much to take in. Drops of amacha splattering all around and my surrendering to not being able to drink even a fraction of them in. For Sergio, it was just another day’s work.

He told me to come back in the morning. The time to open the kiln. The moment to see what the shock of the temperature change had done to the pieces—or whether they have survived at all.

I thought of my little bambino as I fed the dragons that night. I asked the bowl in my mind’s eye what I asked them when they were just tiny beans in a belly:

“Do you want to exist?”

Bowling

The following is a page typed up from my handwritten ceramics journal.

Wednesday April 9, 2025 – 9:42 AM

I am in the tearoom now. Shortly, I will walk up to Sergio’s and open the kiln. What will be the result? Not just of my chawan or his pieces or the fire. But of what ceramics will or won’t do to my life? Does it want me? Three times, in three phases, there has been a disaster/mistake and each time a reinvention. A twist. Turn. A twirling into something more beautiful. A new story, as Sergio might say. It’s not meeting my twins for the first time but it’s more like that than not. Should I expect something? Nothing? Slowly, slowly, Sergio might say. Should I bring matcha to prepare in the freshly hatched bowls? A camera? Tea to share? Plot? Scheme? Be? Just be, maybe the hardest and easiest thing to do. Maybe this is no time for a fountain pen. How I wish my father had found ceramics. How I wish I had listened carefully to him the way I listen to Sergio now.

That’s it. That was the end of the journal entry. I went up to Sergio’s after that.

My bowl had survived. All of his bowls, too. The dark smoke had been a good sign after all. The colors were vivid and stunning. We looked at all of them. How could I see each as anything but the masterpiece it was?

I took my own bowl in my hands. After 15 years of drinking matcha daily and 15 hours of tiptoeing through the work I had it. My first chawan. My bambino. Sergio told me there were some tiny cracks. Memories of the journey. Some places the glaze didn’t cover on the bottom. Places where liquid may leak into porous places if left long enough. He explained a Tibetan technique using butter. Then, another, using—get this—boiled, spent tea leaves. A method that, if you’ve been following closely, I’ve essentially been preparing for all winter.

It was never finished after firing. It will continue to change until it becomes ash or blossoms, like us all, once again. It made me wonder about stories and endings and what else can come back to life even when death seems final.

Maybe those sealing phases will come. Maybe another disaster will come. The dragons are becoming ever more mobile by the day. Grabbing vinyl players, curtains. Only a matter of time before they can figure out the door to the tea room.

All I could do at the time was ferry the chawan back home. I was exhausted after waking up at 4:00 to watch Declan Rice score two free kicks for my beloved Arsenal against the evil empire that is Real Madrid. I may be dee[ on a tea journey but I’m still a multi-flag-flying freak with banners a flutter all over my souldrums.

I napped that afternoon. When I woke, I made tea for the first time in my chawan. Bambino Cha. Baby tea.

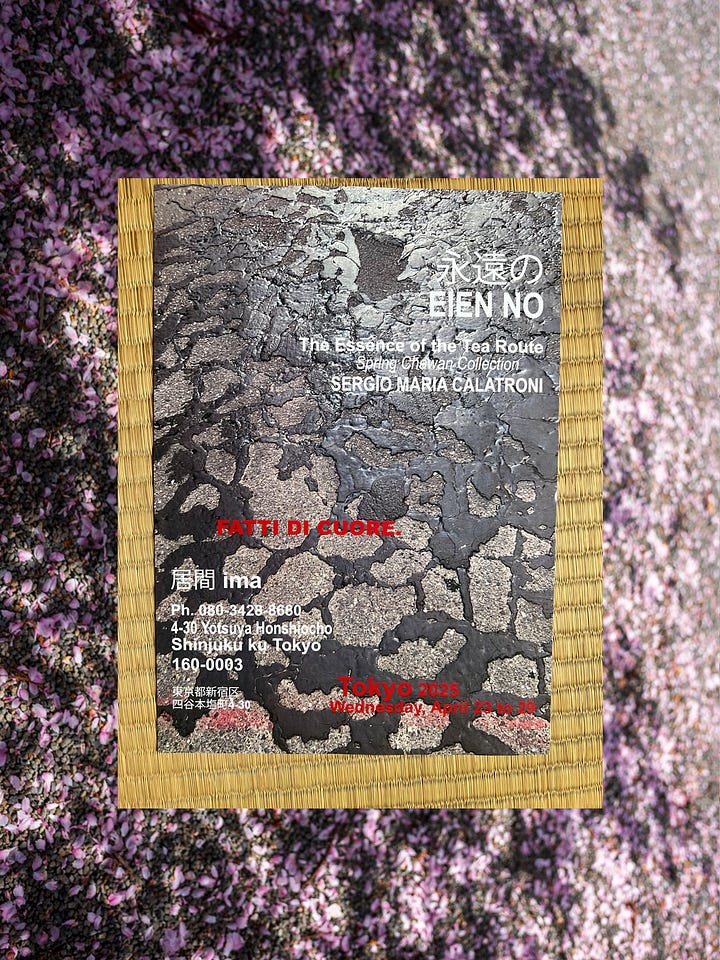

For those in Tokyo, the info for Sergio’s spring chawn exhibition is as follows — it is not to be missed:

Exhibition name:永遠の “EIEN No”

Gallery: 居間 ima

Location:東京都新宿区四谷本塩町4-30

Dates/Time: Wednesday April 23 to Tuesday April 29, 11:00-18:00

My one-take, stuffy nose reading of this month’s poem: “Unfit 4 Obit”

Unfit 4 Obit

Warning: this obit is unfit

for granola.

Apologies: I’m only a student

of Snacking as Midmorning

Ceremony

Admission: this practice—I only

realize now, as I write for the living

about the newly deceased—was

born from the newly deceased

Confession: a tactic to be like them,

to follow them, to chew

on their wisdom.

Aspiration: to be them.

Confidence: to copy

them down to their

bellies. cores. guts.

Bits.

Caution: a heart

has tipped over

and spilled its canteen

contents in a desert

world where words

have become sand

—and silence oasis—

here

the only grains we have

cannot nourish us

the only grains we have

cannot nourish us

the only grains we have

can become glass.

Question: if this obit

was only granola bits

might we better heed

how to carefully carry

ourselves toward 100

with the hourglass-tiny

tactics of our unnamed

hungers and thirsts

might that better honor

the newly deceased?

Answer: Do you mean

honor as much or more

as never finishing

their endless book

before they died?

Question: Does that book

now go on forever?

Answer: You have granola

bits in your beard.

"there is an invisible stack of books next to my bed—all those stories my own loved ones never wrote down"

Thought-provoking line. We're looking forward to the Baille beats.

"Afraid of the clicks on a tiny camping stove."

LOL we gotta get you out (back)camping sometime.

Cool to see the pottery journey. Drink every cup as if its your last, meet everyone as if you're meeting them for the first time..I'm finishing up this amazing 2002 Fuhai we bought shortly after I mailed my stuff out to you. Always restores, invigorates, hard to find stuff like this..

"Ota: Why are we afraid of the first time? Every day in life is a first time. Every morning is new. We never live the same day twice. We're never afraid of getting up every morning. Why?"

-YiYi